Gut Primacy: The role of Intuition in Decision-Making

Have you ever taken a bite of a sandwich only to realize it's disgusting? Or physically distanced yourself from a foul stench? There’s very little one can do to change one’s disgust toward rotten food or a stench in the hallway. There are evolutionary psychological forces pressing us to move away or toward objects (people, places, things) in space. We don’t need to give these intuitions much thought in order to act upon them, as they occur rapidly even before we are fully conscious of them.

Understanding intuition and its primacy in decision-making is critical to understanding human behavior. For example, undergirding every advertisement, every marketing promotion, sale, offer, product showcase, and beneath every experience is a set of affects being communicated to and from the audience. I will use ‘emotions’ and ‘affects' interchangeably to reference manifestations of one’s emotional state. Understanding affect primacy is the superpower of every storyteller, experience designer, and successful offering of products and services in the market.

My aim is to provide a rapid survey of the empirical research on intuition and affect as it relates to decision-making. This research can be used in a variety of applications and use-cases across industries. The article will explore the evolution of intuition research from its early empirical roots, through Zajonc's pivotal contributions, to modern findings.

Early Empirical Explorations of Intuition

Before there was behavioral economics, there was William James. In The Principles of Psychology (1890), James recognized the immediate, non-rational feelings we now call intuitions. He spoke of "intellectual sympathies, fancies, ways of thinking," highlighting the presence of direct, often unexplainable, cognitive experiences. James's focus on the 'stream of consciousness' acknowledged the existence of mental processes that bypassed conscious reasoning, laying a foundational understanding of the rapid, pre-cognitive nature of intuitive responses.

Not much later, in the early 20th century, Gestalt psychology further illuminated the concept of intuition through its emphasis on 'insight' and holistic perception. Max Wertheimer, a key figure in this movement, explored how problem-solving often involves sudden, non-linear leaps of understanding, rather than step-by-step analysis. His work demonstrated that the human mind has a propensity to perceive and comprehend wholes, rather than isolated parts, suggesting an intuitive capacity for recognizing patterns and relationships. This highlighted the brain's ability to intuitively grasp complex situations, a crucial aspect of intuitive decision-making.

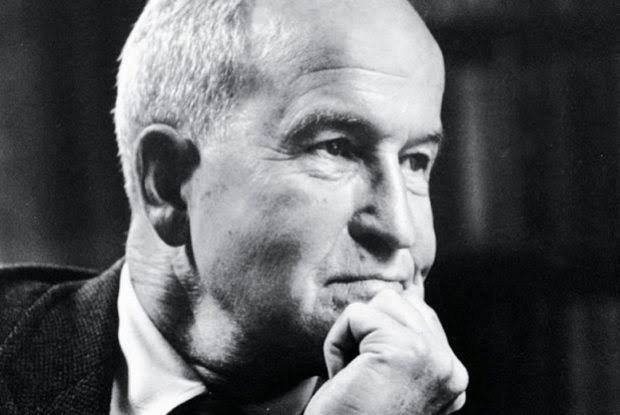

Later, Henry Murray, in his groundbreaking work Explorations in Personality (1938), delved into the realm of implicit motives and unconscious drives. His development of the Thematic Apperception Test (TAT) provided researchers with a tool to explore non-conscious motivations and emotional responses, revealing the hidden influences that guide human behavior. Murray's research acknowledged that many decisions are driven by factors outside conscious awareness, aligning with the concept of intuition. By investigating the 'needs' and 'presses' that shape personality, he indirectly shed light on the role of implicit feelings and 'gut reactions' in decision-making, further contributing to the growing body of empirical work that recognized the importance of non-rational processes in human behavior.

Photo of Henry Murray courtesy of: https://www.harvardmagazine.com/2014/02/henry-a-murray

Zajonc's Affective Primacy: The Feeling Before the Thought

Then came Robert Zajonc, shaking things up with his 'Preferences Need No Inferences' paper. He showed us this 'mere exposure effect,' where we like stuff more just because we've seen it before, even if we don't remember it. Zajonc basically said, 'We think we're logical, but our feelings often call the shots.' He proved that gut reactions can happen before we even start thinking, which was a big deal, because everyone thought thinking always came first.

Zajonc flipped the script, proving emotions aren't just a sidekick to our brains. He showed us feelings can run the show, influencing our choices without us even realizing. He put a spotlight on how fast and automatic our emotional responses are, showing that our 'gut' often knows what it likes before our brain catches up. This work gave us solid proof that intuition isn't just some fuzzy feeling, but a real, powerful force in how we decide things.

Image Courtesy of: https://www.psicoactiva.com/biografias/robert-zajonc/

The Rise of Dual-Process Theories

Kahneman and Tversky made a major contribution to intuition research with their 'System 1' and 'System 2' findings. Click here to read my article on the two systems. System 1? That's our gut, quick and automatic. System 2? That's the brain working overtime, slow and logical. They showed how we use 'heuristics' – mental shortcuts – and how feelings often steer us wrong. Think of the 'affect heuristic,' where we decide based on how we feel about something, not the facts. Basically, they gave us a map of how our brains do the fast, feeling-driven stuff, which is a big part of intuition.

They proved how intuition isn't just a random hunch. It's a whole system, working fast. They showed how our brains are wired to jump to conclusions, often based on emotions, and how that impacts our choices. They proved, like Zajonc and James postulated, that we're not always these hyper-rational beings we think we are. Instead, we're often running on autopilot, letting our feelings guide us. And that autopilot? That's intuition, plain and simple.

Neuroscientific Insights into Intuition

Then the brainiacs with the fancy scanners (fMRI) jumped in, showing us what's actually happening when we go with our gut. It turns out, it's not just some magical feeling – it's our brain's fast track. The amygdala, that's our fear center, fires up quickly, and other parts, like the insula, help us feel those 'uh-oh' or 'yes!' vibes. They showed how our brains pull together feelings and senses in a flash, giving us that instant read on a situation. It's like our brains are saying, 'Don't think, just feel this one.

They also found our bodies get in on the action, too. Our heart races, we get goosebumps – that's our autonomic nervous system, chiming in with the gut reaction. These brain scans and body signals showed intuition isn't just in our heads; it's a whole-body thing. Our brains and bodies are working together, quickly, to give us that instant feeling, that 'knowing' without knowing. It's not magic, it's just really fast brainwork.

Contemporary Research and Applications

Lately, researchers are digging deeper into how intuition plays out in real-world decisions, especially in complex areas like finance and medicine. They're finding that experts, the folks who've seen it all, often rely on 'skilled intuition.' It's not just a random hunch; it's pattern recognition built from years of experience. Think doctors who just know something's off, or traders who sense a market shift. Turns out, intuition isn't just a wild guess; it's a super-fast way of processing tons of info, and experts are getting really good at it. They're also exploring how mindfulness and other techniques help people tune into their gut feelings, making those intuitions even sharper.

Another hot topic is how we can tell when to trust our gut and when to slow down and think. Researchers are looking at how emotions impact our judgment, and how we can learn to spot those biases. They're showing us that intuition can be awesome, but it's not foolproof. They're figuring out ways to combine that fast, intuitive thinking with some good old-fashioned analysis, creating a kind of 'best of both worlds' approach. It's not about ditching logic, but about knowing when our gut's giving us good info, and when it's leading us astray. This research is helping us build a smarter, more balanced way to make decisions, blending the power of intuition with the clarity of reason.

Conclusion

So, what's the takeaway? Well, we've seen that intuition isn't just some fuzzy feeling – it's a real, powerful tool in our decision-making toolbox. From the early days of James and those Gestalt insights, to Zajonc's game-changing work, and all the brain scans and behavioral studies since, we know our guts are smarter than we often give them credit for.

Ultimately, we're all walking around with this amazing built-in system, a kind of 'smart gut,' that can help us navigate the world. The trick is to learn its language, and to use it wisely. So, next time you get that feeling, don't just brush it off. Take a moment, listen, and see what it's trying to tell you. You might just be surprised at how smart your gut really is.

References

Bechara, A., Damasio, H., Tranel, D., & Damasio, A. R. (1997). Deciding advantageously before knowing the advantageous strategy. Science, 275(5304), 1293–1295.

Damasio, A. (1994). Descartes' error: Emotion, reason, and the human brain. Putnam.

James, W. (1890). The principles of psychology. Henry Holt and Company.

Jung, C. G. (1969). The archetypes and the collective unconscious (2nd ed.). Princeton University Press.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Lieberman, M. D. (2007). Social cognitive neuroscience: A review of core processes. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 259–289.

Murray, H. A. (1938). Explorations in personality. Oxford University Press.

Slovic, P., Finucane, M., Peters, E., & MacGregor, D. G. (2002). The affect heuristic. In T. Gilovich, D. Griffin, & D. Kahneman (Eds.), Heuristics and biases: The psychology of intuitive judgment (pp. 397–420). Cambridge University Press.

Wertheimer, M. (1923). Untersuchungen zur Lehre der Gestalt, II. Psychologische Forschung, 4(1), 301–350.

Zajonc, R. B. (1980). Feeling and thinking: Preferences need no inferences. American Psychologist, 35(2), 151–175.